Father’s Day isn’t easy for me.

There are many reasons starting with a father-absent childhood and the depressing jealousy watching daddies and daughters live out a fantasy I’d never have – all the way to the recurring life-theme of pushing away deep relationships to save myself the embarrassment, shame, and agony of potential abandonment.

And now that I’m divorced, we can add another reason for me to want to get the day over with. I don’t want to think about not celebrating this day with the father of my children because we just don’t have that kind of relationship. I honestly just want to go back to work. Or go off the grid. Maybe next year I’ll find a cabin in Alberta for the weekend. Alone.

However, the following story reminds me to be less sad on Father’s Day and be more accepting of the love that DOES surround me everyday – if I choose to see it. Every piece of it is true and straight from the supernatural energies the swirl around us.

Now I try to celebrate Father’s Day by remembering that magic is real and forgiveness can communicate, even beyond the grave.

So Happy Father’s Day to all the dads – the great ones and the not-so-great ones. And to the kids that struggle with this like I do, well…you’re here, in part, thanks to your dad’s super swimmers. Hating/detesting/resenting him only means you’re letting a part of yourself rot right along with your esteem of him. Might as well accept it, make peace with it, and then make the most of it.

This story, “February” is a short piece I wrote about eight years ago. Hope you enjoy it.

FEBRUARY

Thrilled to be living abroad for the semester, I planned to go to the south of France for winter break with my best friends Anne and Ryan. Mom called the weekend before our departure and said she spoke with Dad. He didn’t sound well, she had said. She asked if I wanted to come home and see him instead of going on vacation. I said no. Well, call your father, she said. I said no.

* * *

My father, James Reese, was very active in the community. In the seventies, he and my mother had a radio show together. I’m told he was called ‘the velvet voice of Detroit,’ for his smooth baritone vocals and charming radio personality. They also owned and operated an adult life and career counseling center called M.O.R.E: Mobilizing Our Reserve Energy.

He was my world as a small child. I was full of hope and my eyes twinkled when I heard his voice. But things changed by the time the eighties rolled around. The success vanished. They said he changed. My parents divorced when I was two years old, and I have no memory of them ever living in the same house. For as long as I could remember, he lived in Ohio.

He was my world as a small child. I was full of hope and my eyes twinkled when I heard his voice. When I missed him the most, I would listen over and over again to his recording of a black empowerment poem, I Am The Oppressed. I wrote him letters too, many of which were never sent.

Daddy, when are you coming to visit, most said. Don’t forget, it’s my birthday soon, I would write. Daddy, it’s almost Christmas. Are you coming home? When will I see you again? I have a dance recital, Daddy. Are you coming to it? Daddy, I just finished another Suzuki book. When will you hear me play the cello?

Many of the replies listed a thousand excuses, but always closed with I’m working on something now; we’ll have a lot of money soon. Pray for Daddy.

He was my world as a small child. I was full of hope and my eyes twinkled when I heard his voice. He did visit sometimes; every few years or some other irregular pattern. The years came and went, many letters exchanged, all the same. Many promises of frequent visits. Promises to send money. Promises that things would change. All of them empty.

In high school, I gave up on having the illusion of that dream daddy-daughter relationship. I gave up on the letters. I gave up on the phone calls. I lost the recordings of his voice. Hey dad, I would say on the occasional brief telephone conversation, so… can I have some money? Hey pop, wanna get me a car for my sixteenth? Hi dad. Yeah, well… uh, I gotta go. It was strained, tense. Forced at best. I gave up. I couldn’t understand why he didn’t care. Apathy was my weapon of choice against the pain. By my last year of high school, it was fifteen years of private cello lessons, practicing, orchestras, camps, recitals, international tours, sixteen years of ballet jazz and gymnastics, countless sports games, college level Calculus, all of this he had never seen. Finally my high school graduation, I didn’t ask him to come. He did manage to come up for that, the first time he ever heard me play the cello.

The summer before my junior year of college, Mom and I went to visit my brother and sister-in-law in Ohio. Dad moved close to them thanks to brother’s coaxing. It was the first time I had seen him in about two years. He looked old. He was already an old man, something like fifty when I was born. But now he looked really old. He tried to give me stuff. Just stuff. Old piano books, his keyboard, a print of a painting and other random things I didn’t really want. But I accepted them. By my junior year of college, I had plans to study abroad. I went to Rennes, France for my spring semester.

* * *

Two days later, Mom called in the morning after my first Monday morning class at l’Universite d’Haute Bretagne. She said something was wrong but she didn’t know what. She would call again. We had a break between classes that morning, and it was a beautiful day. Anne and I were getting so excited for our excursion south, we decided to ditch the next class and take a walk through the park. The bright sun, the sound of falling water in the fountains, the slight rustle of leaves blowing in the fresh spring breeze all tried to hide me from the pang of fear lurking in my heart and tears burning in the backs of my eyes. I knew Mom would call soon. And she did.

I heard the gasp and the 24-hour second of hollow silence that comes before that first big drop in a roller coaster, followed by the struggle for breath to let out a blood-curdling scream. It was the swoop without the thrill and laughter. The ground fell and my stomach dropped with it. I crumbled onto the gravel park floor. I was sure it wouldn’t catch me.

I pretended for so long that I wouldn’t care until he cared. That I wouldn’t love until he loved. But I did. I cared. I loved. And I wanted my Dad. I wrote another letter that night; another letter I would never send:

Dad, I waited for you. I waited for you to come to me and be ready to be my father. I wanted you to make it work and to walk me down the aisle. I wanted you to love me and be proud of me. I wanted you to go everywhere and say “Look at my beautiful family. Look at my beautiful daughter. I love her and I am proud of her.” But you didn’t.

Ryan met up with Anne and me for a few silent mournful kirs. They stayed with me all night. Neither forced the words that would never come out the right way. We sat there in silence, save my un-suppressible fits of sobbing that would strike at any random moment, until we fell asleep. I didn’t go to the south of France. I left the next morning for Detroit.

* * *

After the terrible week at home consisting of finding out that Dad died alone in his small apartment that had already reeked of death, that he had a few distant relatives that had to be retrieved to fill a total of ten seats in a small memorial chapel, and that he was cremated because he was found one or two days postmortem, I went back to France eager to get on with my life.

When May came around, I realized I had over packed– I went home with a small carry-on for Dad’s memorial service, and came back with my cello and a large suitcase. I began to mail boxes of my belongings from France to my anticipated self in Detroit. I had been home for at least a week or two before the boxes started to show up one at a time. They all made the journey except one. I figured it was a sign from God that I had way to many clothes for one person and I should accept the loss as encouragement to downsize my closet. I think God had a hand in it all, but the message was not about my closet.

The box showed up a few weeks later, but it did not arrive as it was sent. While the other boxes knocked on my front door looking like old men who had seen one too many hard days in their long lives, the last box was brand new, large with crisp un-bashed-in corners, and wrapped with plastic twine like a gift. On the box was a note from the postman: We apologize but your parcel was damaged en route beyond repair. We hope this contains your items, but are not responsible for any lost or damaged articles. I tore open the box like it was Christmas.

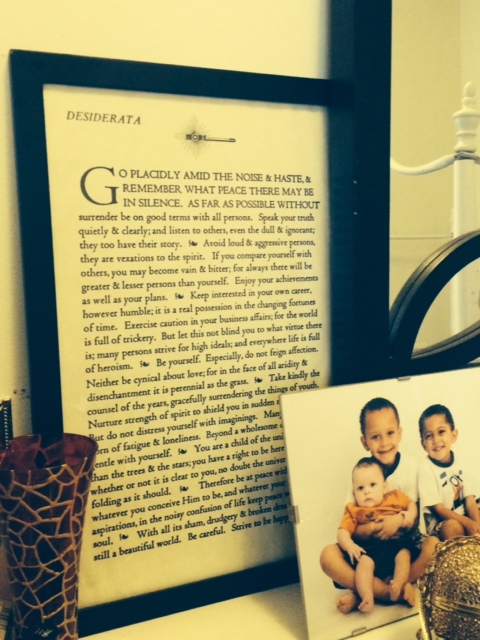

I was reunited with sweaters, shoes and shirts I thought I would never see again. We hugged and laughed about old times. All of my belongings were accounted for, but there was more: a box of Toffiffee candies, some amateur photography, some intricately patterned tattoo-like doodles, a copy of Dante’s Inferno, a few Grateful Dead records, a handwritten copy of DESIDERATA.

Desiderata. Desiderata. It was everything I was looking for at that time in my life; the time when everyone looks for direction aside from blind faith in what our parents taught us about life, love, and religion. I was searching for meaning aside from religious doctrine flooded with room for human error in interpretation. I remembered Shusaku Endo in Deep River writing, “There are varying degrees of truth in all religions. All religions spring forth from the same God. But every religion is imperfect. That is because they all have been transmitted to us by imperfect human beings.”

How much of Truth is lost in translation? I wondered why Creator left it up to us dumb humans to try to translate Life into our own simple comprehension. If it is one God speaking to all of us around the world, then why do so many religions contradict each other? I look to the Bible for inspiration, direction, and guidelines, but what about my other friends who turn to other doctrines, up to and including Dr. Seuss? How could we engage in deep philosophical discussions if one side is faithless in the other’s foundations of thought? How would we coexist under the umbrella of pure inborn human laws that are not implied by an organized faith? I had asked God for a summary. I asked him for a philosophy of life so simple and unattached to any religion that every sane human can effortlessly agree that this is what Life is about. This time, my wish was His command. Tangibly delivered into my hands.

I took Desiderata with me everywhere, pinning it on the wall above my bed while I worked at camp that summer, then to the wall above my bed in my apartment to close out my senior year of college. In 2005, I focused my college exit paper, my Philosophy of Life, on my relationship with my father, the fact that I had never really grieved him, and how I had come to find closure with his death. I concluded the paper with my narrative of how Desiderata came to me in 2004.

I wrote: Desiderata was my little present from God. It was beautifully scripted on cloud-print paper, emphasizing its supernatural state. I was so excited. I had been thinking of how I could summarize my beliefs, my passions, and my mystic view of life. This was it …I read the poem and I said out loud smiling towards the sky, ‘Thank you’. I read Desiderata so many times it was partially committed to memory. It had become such a part of me that one familiar word in an unrelated conversation triggered a flood of phrases from the poem that I would recite over and over in my head. I made copies of it and passed it on to my classmates during my Philosophy of Life presentation. I loved Desiderata.

Having its impression on my heart, I had realized the painful truth: I never really did trade optimism for apathy. I used apathy as a cover to avoid getting hurt, just in case Dad never had a stroke of courage to develop a bond with me. I was devastated with his death; not mourning the loss of a great life full of memories, but having the potential of Daddy-daughter redemption stripped away from my soul. Ultimately, I came to peace with Dad within myself. I forgave him for not being the 100% Daddy that I wanted, and I forgave myself for not rushing home to see him one last time. I thanked God for sending Desiderata to help me retrieve my childlike optimism about life and love.

It was 2005 and I was graduating from college. After commencement, my family gathered in a hotel room to have a bit of a celebration complete with champagne and gifts. I opened a card from my godmother Aunt Marcy.

I heard the gasp and the 24-hour second of hollow silence that comes before that first big drop in the roller coaster, followed by the struggle for breath to let out a blood-curdling scream. It was the swoop with all of the thrill and laughter. The ground fell and my stomach flew up into my throat. Inside the envelope was a wallet-sized excerpt from Desiderata. I glanced blankly back and forth between the wallet card and Aunt Marcy’s face.

“I looked all over for it,” she said, “It was the last one.”

“Did I tell you the story about this?” I sputtered out.

“No…”

I began to recant from the part about having too many clothes. After I closed with the part about passing out copies to my fellow students, Mom looked at Aunt Marcy and said, “Should I tell her or should you?”

Aunt Marcy smiled and said, “You should”.

“Remember how I told you about M.O.R.E.,” Mom began. “Your father and I used to teach a class on this poem. It was his favorite poem. He used to read it to you when you were a baby.”

A few years afterwards, my mom found copies of Desiderata, branded with the M.O.R.E. logo, just like my dad had designed. I keep one framed in my bedroom.

to read all of Desiderata, click here

Happy Father’s Day, dad.

~OR